0

A Demented Doctor’s Legacy

Definition of Tragedy: The Life of Dr. W. C. Minor

William Chester Minor spent the first years of the Civil War studying medicine at Yale. Following graduation in February 1863, he became a surgeon in the United States Army and underwent training in New Haven, where he worked with recovering soldiers.

As Grant and Lee battled in the Wilderness in May 1864, Minor was sent to the Virginia front. There the young doctor, a gentle soul who loved books and painted watercolors, dealt with the grotesque effects of minie balls and schrapnel on the human body. Later he would work at hospitals in and around Washington.

Minor remained in the army after the war, eventually becoming an officer and earning a brevet promotion to captain for his work during an 1866 cholera epidemic in New York.

Just as the doctor’s professional life seemed secure, his personal behavior set him on a course with disaster. Minor began frequenting bars and houses of prostition in the slums of New York and felt the need to carry a gun for protection. His superiors transferred him to Ft. Barrancas, Florida on Pensacola Bay, apparently hoping duties as regimental physician for the remote post would keep the young doctor from temptation, place little pressure on him, and effect a recovery.

After madness turned promising army surgeon William Chester Minor into a murderer, the Oxford Enslish Dictionary brought meaning to his life.

The assignment, however, failed to solve Minor’s problem. He suffered from headaches and dizziness (possibly the result of sunstroke) and began showing signs of paranoia. Sent back to New York in 1868 for medical examination, he was diagnosed as obsessive/delusional and ordered to a federal mental hospital in Washington, D.C. Minor did not disagree with the diagnosis or that he needed to be institutionalized. He did, however, ask that he be allowed to make the trip from New York to Washington alone. Amazingly, his request was granted. Even more amazingly, he kept his word.

As doctors endeavored to treat his condition, Minor earned their respect to the extent of being trusted to leave the hospital grounds. Still in the military, he went downtown to pick up his pay each month.

The doctors worked with Minor for over a year before concluding that he could never be cured. He was retired from the service in April 1869, retaining pay and pension priveleges for the rest of his life.

In 1871, Minor spent the summer and early fall with family members in New Haven, disturbing them with claims that each night sinister individuals entered his room and violated him in bizarre manners.

According to Simon Winchester, author of The Professor and the Madman, Minor felt he was being punished for “an act he had been forced to commit while in the Amercian army,” presumably branding a “D” on the cheek of an Irishman convicted of desertion.

Minor determined he could escape his malevolant persecutors by crossing the Atlantic. He was on his way to London in October 1871, saying he intended to spend a year or more in Europe where rest, reading, and painting would restore his health.

Minor may have believed what he proclaimed, and his family undoubtedly hoped he was right, but Europe proved no more a healing venue than had Fort Barrancus. Initially, Minor’s situation seemed hopeful. He stayed at a West End hotel in London and traveled by train to several cities on the continent. Using a letter of introduction from a Yale connection, he met the critic and artist John Ruskin. However, his paranoia continued, and he repeatedly reported to police that his rooms had been broken into, probably by Irishmen.

Another aspect of Minor’s deteriorating mental condition– his obsession with prostitutes– also exterted itself. He moved from the West End to a squalid working-class community on the edge of London. By day vapors spewing from the unattractive industries of Lambeth Marsh polluted its air; by night taverns, bawdy theaters, and brothels polluted its moral atmosphere. William Chester Minor immersed himself in the seamy lifestyle. And in the early morning of February 17, 1872, he killed a man.

*****

Hearing shots, policemen quickly arrived at the spot on Belvedere Street where one man lay bleeding while another stood nearby holding a revolver. The victim was a 32-year-old brewery stoker on his way to work the early shift. Minor admitted to having shot the man but claimed he had mistaken the stoker for an intruder who had broken into his room. He was, nevertheless, charged with murder.

The investigation of what newspapers called the Lambeth Tragedy and the subsequent trial of Dr. Minor drew media attention on both sides of the Atlantic. According to an article published in the South London Chronical a week after Minor’s arrest, United States Vice-Consul John Nunn and De Tracey Goued of the American Bar sat in on the police court’s examination of Minor.

At Minor’s trial, his army records, along with testimony from his landlady, his stepbrother, London policemen, and others convinced a jury to declare on April 6, 1872, that William Chester Minor was innocent of the crime of murder by reason of insanity. The judge ordered that the doctor be institutionalized “until Her Majesty’s Pleasure be known.”

The institution to which Minor was sent was the Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane in Crowthorne, Berkshire, England. It was not a hospital, but a prison whose residents were locked in cells and referred to as lunatics. However, it represented the best Britian had to offer the criminally insane based on enlightened attitudes advocated by Dorothea Dix and other nineteenth-century reformers.

Less than ten years old when Minor arrived on April 17, 1872, Broadmoor segregated its inmates according to gender and level of violence. Block 2 was reserved for non-violent men with financial and/or political resources. Minor qualified on all accounts. Except for believing strangers often entered his quarters in the nighttime, he was lucid, even charming, given his knowledge of literature and art. His yearly Army pension of $1,200 permitted him to occupy and furnish two adjoining cells on the top floor. Vice-Consul Nunn interceded on Minor’s behalf and received persmission for the doctor’s clothing and personal effects, including his art supplies, to be sent to Broadmoor. According to Winchester, the Vice-Consul also arranged with prison officials for Minor to be supplied with “whatever he liked so long as it didn’t prejudice his safety or the asylum’s disciplined running.” Whatever Minor liked included wine and bourbon.

Minor also liked antiquarian books and had his sizeable collection shipped from the United States. He also ordered other volumes. Eventually his library grew to the point that he paid to have floor-to-ceiling bookshelves installed in one of his cells.

For eight years Minor led a rather comfortable life at Broadmoor. During the day, the cells on the top floor of Block 2 were unlocked to permit inmates access to bathroom facilities, a situation that allowed Minor a certain amount of conversation with his peers and the floor guard. Doctors visited him, prescribed medications, and kept notes on the his progress. He received visitors occassionally and was often permitted to walk the prison grounds. He even hired another inmate of Block 2 as a housekeeper.

Minor’s life improved in the early 1800’s when he found a flier in one of the books he had purchased. It was an appeal for volunteers to assist in compiling a dictionary to trace the history of word usage by documenting the introduction of each word into the English language and each shift of meaning with passages from literature. The advertisement had been placed by the man who assumed editorship of the project in 1879, Dr. James Murray. Knowing the compilation of what would become the Oxford English Dictionary would require decades, Murray used the media of his day– newspapers, magazines, and fliers– to enlist the aid of thousands of volunteer readers. Minor, who loved reading, had an impressive library of antiquarian books, and unlimited time for research, filled out the application and sent it to Murray.

The application was accepted, and Minor began reading and documenting words, a task he would continue for twenty years. Murray generally asked volunteers to look for particular words, but Minor developed a method of taking notes on many words as he read. Thus, when Murray asked for information on a particular word, Minor likely had a file already compiled on it and could respond quickly. He soon became one of Murray’s most dependable and proflic contributors. His work and Murray’s expressed appreciation of it brought meaning to Minor’s life.

Because Minor always gave Broadmore as his return address, Murray assumed that Dr. Minor was on staff there. In the late 1880’s Dr. Justin Winsor, the librarian of Harvard College, visited Murray. While discussing the progress of the dictionary project, Murray mentioned Minor’s invaluable work. Only when Dr. Winsor apprised him of Minor’s background, did Murray realize his best contributor was an inmate.

This knowledge created a dilemma for Murray. As Minor never referred to his personal situation, Murray thought it improper for him to bring it up. Winchester quotes him as saying, “. . . all I could do was to write to him more respectfully and kindly than before. . . .” Fortunately, another American guest, one who had visited Minor at Broadmoor, assured Murray that Minor believed the editor had always known of the incarceration. This revelation prompted Murray to write the warden at Broadmoor to arrange a visit with Minor.

Dr. Minor received Dr. Murray for the first time in January of 1891; other visits followed over the next twenty years as the two men shared their similar interests in words, books, and art.

*****

Regrettably, having a new purpose and a new friend in his life could not dispell the demons that haunted William Minor Over the years, his delusions grew more fantastic. (After the 1903 success of the Wright Brothers made aviation a reality, Minor said his persecutors transported him by airplane to distant locations.)

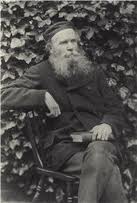

By the turn of the century, Minor was sixty-six, a bushy-beared old man. Doctors had been unable to cure his illness or even keep it at bay, and in 1902 he amputated his own penis. Time marched on; Minor grew infirm and could no longer research words for Murray. His one remaining joy was painting, but in 1910 a new director of Broadmoor, a man much less compassionate than his predecessor, rescinded all of Minor’s privileges. The doctor had to give up his double cell, his books, and his painting supplies.

For some time friends of the doctor, including Murray, had worked to have Minor released from Broadmoor so that he could spend his last years in America near relatives. They redoubled their efforts once Minor was placed in a single, unembellished cell. The doctor’s brother arrived in London a few weeks later, prepared to accompany Minor to the United States where he would be placed in St. Elizabeth’s Federal Hospital, the same Washington, D. C. facility he had entered in 1868.

All that was needed for Dr. Minor to go home was authorization from the British government. It came on April 6, 1910 when the home secretary, Winston Churchill, signed a Warrant of Conditional Discharge. The condition was that Minor would never return to the United Kingdom. Ten days later, William Chester Minor left Broadmoor where he had spent thirty-eight years, half of his life.

Minor spent nine years at St. Elizabeth’s, during which time his physical and mental conditions both deteriorated. In 1919 a nephew secured permission from the army to have Minor released from federal custody and placed in a hospital for the elderly insane in Hartford, Connecticut. There the doctor, still tormented by his insanity but proud of his thousands of contibutions to the Oxford English Dictionary, died on March 26, 1920.

___________

The conclusion by United States Army doctors that Dr. Minor’s mental problems were triggered by his involvement in the Civil War, was probably an oversimplification. In The Professor and the Madman, author Simon Winchester presents several aspects of Minor’s early life that likely contributed to his instability.