0

Brawn and Brains Netted Union Prisoners Better Rations

In the spring of 1862, Stonewall Jackson outgeneraled Nathanial Banks to keep Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley under Confederate control. The First Battle of Winchester, fought May 23-25, resulted in a lopsided rebel victory that saw approximately 1,700 Yankees captured and taken to Richmond. Among them was David Van Buskirk of the 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. He was the tallest soldier in the Union army– and he may have been the only man to have gained weight while incarcerated in the infamous Libby Prison.

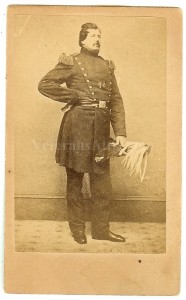

Lieutenant David Van Buskirk enjoyed celebrity status while incarcerated in Richmond’s Libby Prison.

Standing 6’10” in stocking feet and weighing 380 pounds, Van Buskirk was understandably conspicuous among the captives being herded through Richmond’s streets to their assigned quarters. Lieutenant Van Buskirk went to Libby Prison, a former tobacco factory housing captured Federal officers. Curious civilians applied for visitor passes to enter the prison to see the man dubbed “the biggest Yankee in the world.” Even President Jefferson Davis drove to Libby to interview Van Buskirk. Because having civilians streaming through Libby proved inconvenient, the giant was sometimes taken outside the prison and paraded through the streets to give Richmonders more opportunities to see him.

Ultimately, someone decided to turn the large lieutenant into a cash enterprise. Whether the plan was officially approved or simply officially ignored, the Yankee Goliath became the star of a freak show. In return for being put on display, Van Buskirk asked only that he be given all the food he could eat. His request was perfectly logical for two reasons. Libby had been notorious for scant rations of poor quality since it began receiving prisoners after the Battle of First Manassas in July 1861, and Big Dave required more nutrition than the average soldier. He also had an advantage over his money-hungry captors: A shrinking giant would draw few admission-paying gawkers. Van Buskirk’s strategy worked. When he was exchanged in September 1862, he weighed over 400 pounds.

The war dragged on, and a steady steam of Federal captives strained Richmond’s prison system. When Private John McElroy arrived in early January 1864, he was confined with 1,100 other soldiers, sailors, and marines in the Pemberton Building, another converted tobacco factory only a stone’s throw from Libby Prison. All of them hoped to be exchanged as Van Buskirk had been in 1862, and when many of them were marched to a railhead early in the morning of February 18, they thought their hopes were about to be realized.

The prisoners found themselves packed into boxcars so tightly they could only stand, but they maintained a jubilant mood as they expected Petersburg, only a few miles south of Richmond, would be their place of exchange. Spirits sagged, however, when the train stopped in Petersburg but the uncomfortable prisoners remained confined to the cars. Eventually the train steamed south again, arriving after dark in Gaston, North Carolina, where the prisoners were finally allowed to detrain to receive their only rations of the day– a few crackers.

When being told to board different cars for the next leg of their journey, McElroy and a few of his companions took advantage of the darkness to deceive their captors and ensure a more comfortable ride. In his memoir*, McElroy describes their ploy:

About thirty of us got into a tight boxcar, and immediately announced that it was too full to admit any more. When an officer came along with another squad to stow away, we would yell out to him to take some of the men out, as we were crowded unbearably. In the mean time everybody in the car would pack closely around the door, so as to give the impression that the car was densely crowded.

This scheme permitted McElroy and his cronies to get some rest as the train rumbled its way southwest through the night. It also provided them with another advantage, one that may have helped him survive the war:

We managed to play this successfully during the whole journey, and not only obtained room to lie down in the car, but also drew three or four times as many rations as were intended for us, so that while we at no time had enough, we were father from starvation than our less strategic companions.

The thirty men in McElroy’s boxcar did not then know that rather than being exchanged they were to be among the first residents of a new Southern prison– Andersonville.

*Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Prisons