1

The Feminine Face of the South

The Confederate woman whose face was reproduced thousands of times during the war was unkown to most of her countrymen.

Scarlett O’Hara, as portrayed by Vivian Leigh, symbolizes the Southern belle stereotype for many Americans.

The film version of Margaret Mitchell’s epic Civil War novel Gone with the Wind debuted in 1939. An instant and enduring success, the movie spawned hundreds of books, articles, and collectibles. Now, more than six decades since the film first captivated audiences, it is the face of British actress Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara that symbolizes nineteenth-century Southern femininity for most Americans.

Hers was the most reproduced female face in the Confederacy during the war, but only a relative few of her contemporaries could identify Lucy Pickens.

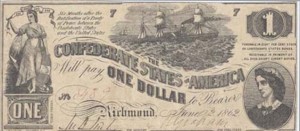

If history were not filled with ironic circumstances, it would be another face– that of a true Southern belle–that would be synonymous with Confederate womanhood. It would be the face that was reproduced more frequently by southern printing presses during the war than that of any other woman. It would be the face of Lucy Holcombe Pickens, the only Confederate woman depicted on currency issued by the Confederate States of America. Beginning in June 1862, Mrs. Pickens’ image graced $1 bills; later the same year, she appeared in a different pose on $100 bills.

Like the fictional Georgia-born Scarlett, Lucy came from the western planter class. She was born in 1832 on her father’s cotton plantation near La Grange, Tennesse, sixty miles east of Memphis. Around 1850, her family moved farther west and established a plantation near Marshall, Texas. Lucy was, however, better educated and more traveled than Scarlett, having attended The La Grange Female Academy whose curriculum included spelling, reading, writing, and French, as well as instruction in drawing, painting, and the pianoforte. In addition, from 1846-1848 Lucy and her sister attended the Moravian Seminary for Women in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, with instructions from their mother to take only strenuous academic classes.

At the Quaker-run school Lucy learned to deal with homesickness and harsh winters, but living in a non-slaveholding society may have provided her greatest cultural shock. However, when her mother took Lucy and her sister on a between-terms visit to friends and relatives in New York, Lucy was impressed by eastern society.

Numerous young and not-so-young men courted the attractive, vivacious, and well-educated Lucy during her late teens. Using her considerable letter-writing skills, she manged to keep her admirers interested without committing herself to any one of them. Unlike Scarlett O’Hara, Lucy Holcombe saw beyond the social scene and developed an interest in politics.

Some sources claim Lucy was engaged to Colonel William Logan Crittenden, a young Kentuckian who participated in an 1851 invasion of Cuba led by the fillibuster General Narciso Lopez. The aim of the expedition was to free Cuba from Spanish rule, a romantic ideal Lucy espoused, not realizing– or perhaps not caring– that Southerners supporting Lopez intened to extend slavery to the island. The invasion failed; Crittenden was captured and executed. In The Free Flag of Cuba or the Martyrdom of General Narciso Lopez, a novel Lucy wrote under a masculine pen name and published in 1854, characters resembling Crittenden and Lucy are romantically linked, but whether they represent reality or are the result of Lucy’s use of literary license is debateable.

At any rate, Lucy was twenty-five and unmarried in 1857 when she accompanied her mother to the Greenbrier resort at White Sulfer Springs, Virginia. There she was wooed by Francis W. Pickens, a wealthy South Carolinian who had served in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the South Carolina Senate, and who was in the midst of a race for the U. S. Senate. Lucy rejected Pickens’ proposal of marriage, possibly because at age 52, he was older than her father, twice widowed, and the father of eight children.

Pickens lost his Senate bid but accepted President Buchanan’s request to serve as the U.S. Ambassador to Russia. He then headed to Texas where he proposed to Lucy again. This time she agreed, apparently enticed by the prospect of participating in the court life of St. Petersburg. Although her parents disapproved of her choice, principally because of Pickens’ age, Lucy and Pickens were wed at the Holcombe home on April 26,1858.

Gossipmongers deemed Lucy a gold digger, especially after she purchased an expensive wardrobe in New York prior to sailing to Europe. However, Pickens’ generous treatment of his bride was likely a combination of love and political savvy. The court of Tsar Alexander II was among the most elegant in Europe; the American ambassador’s wife should create a positive impression.

The young, pretty, intelligent, multi-lingual Lucy became a favorite of the Russian court, particularly of the Tsar and Tsarina, who took a special interest in her health when she became pregnant. When her daughter was born, they bestowed the nickname Douschka, Russian for “darling,” upon the baby and became her godparents. The Tsar began a tradition of giving expensive jewelry to Douschka on her birthday; after his death, his son continued the tradition.

*****

The deteriorating political situation between Northern and Southern states drew Pickens back to America. In April 1860, he resigned his diplomatic post and brought his family home to Edgewood, his plantation near Edgefield in western South Carolina. It was one of several he owned in South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi; their operation required the labor of approximately 500 slaves.

Following Lincoln’s election in November, South Carolina– which had contemplated splitting from the Union for nearly thirty years– held a secession convention beginning December 17, 1860. Three days earlier, the state’s General Assembly, via secret ballot, had elected Pickens governor of the independent state of South Carolina; three days later, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the United States of America.

Pickens had long been a supporter of secession, but he was more diplomat than fire eater. His stance offended more radical separatists, who succeeded in creating a five-member Executive Council to restrict his gubernatorial powers.

One member of the Executive Council was James Chesnut, who had resigned his position as U.S. Senator only days after Lincoln’s election. His wife, Mary Boykin Chesnut, included many references to Lucy Pickens in her now-famous wartime diary, most of them critical.

Chesnut and her circle of friends saw Lucy as a conniving opportunist and an outsider. Yes, she was an ardant supporter of the Confederacy, having sold some Russian jewels to buy uniforms for rebel soldiers; but she was from the West. Yes, she was South Carolina’s first lady; but her husband was being policed by the Executive Council. Yes, she had lived in Russia; but serving tea from a samovar was ostentatious.

Lucy Pickens and Mary Chesnut engaged in two-year battle of oneupsmanship. Lucy unintentionally scored an early point as South Carolinians gathered on rooftops to watch the bombardment of Fort Sumter. She emerged intact, but Mary suffered the indignity of having her dress catch fire as she sat on a chimney. Lucy later scored a deliberate point. While hosting a party, she chose to remain seated when Mrs. Chesnut was presented to her. Lucy used her status as First Lady to embarrass Mary in retaliation for the humiliation James Chesnut and the other members of the Executive Council caused Francis.

By 1862, the Confederacy’s paper money was being engraved and printed in Columbia, the capital of South Carolina. Christopher G. Memminger, Secretary of the Confederate Treasury and a friend of Pickens, decided to

CSA Secretary of the Treasury made the decision to place images of Lucy Holcombe Pickens on Confederate currency.

depict Lucy on $1 and $100 bills. Memminger’s choice was unusual. Until 1862 only allegorical female figures had been depicted on American currency, and it wasn’t until the late 1800’s that the United States pictured a historic woman– Martha Washington– on silver certificates. Why Memminger decided to portray a living woman on bills is unknown. He may have felt that Lucy symbolized the dedication of Southern women to the Confederacy. Or he may have simply have seen her as a convenient model for his Columbia-based engravers. In any case, as Governor Pickens’ term drew to a close and he and Lucy retired from the public life to Edgewood, thousands of bills bearing her image began circulating throughout the South. It is likely, however, that only a relatively few southerners– friends and family members in Tennessee and Texas, along with political allies and enemies in Columbia and Richmond– knew the identity of lady on their currency.

*****

Lucy, Francis, and Douschka spent the remainder of the war at Edgewood, its remote location permitting relatively normal, albeit modest, living conditions throughout the war.

Lucy increasingly assumed financial and administrative respsonsibilities for the family as her husband’s health declined. When Francis died in January of 1869, Lucy, like Scarlett O’Hara, found herself in charge of providing for her family in the difficult post-war environment. Her father had died in 1864, leaving her mother financially insecure; after the war, a ne’er-do-well brother moved in with Lucy. Those of the Edgewood slaves who opted to remain as hired workers also depended upon Lucy for support. The Alabama and Mississippi plantations were gone, but by selling some of her jewelry, Lucy managed to operate Edgewood as a scaled-back subsistence farm. Later, she sold more jewels to finance Douschka’s education.

The Southern economy slowly improved, but Lucy continued to suffer personal losses. Her mother died in 1873, her sister in 1887. A bigger blow came in 1893 when Douscha, who had helped Lucy manage Edgewood, died in her sleep at age 34.

Lucy herself died of a cerebral embolism on August 8, 1899. Her life had been a series of contrasts. Valuing appearances and material objects, the youthful Lucy was self-centered, opportunistic, and sometimes petty, but the mature Lucy gave of herself to others. Concerned not only about the welfare of her family and workers, Lucy engaged in activities on a broader scope. In 1866, she accepted an invitation to become South Carolina’s Vice Regent of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association and worked throughout the rest of her life to restore and preserve George Washington’s home. Always a true daughter of the South, she served as president of a local association which raised funds to erect a monument to the Confederate dead of Edgefield County.

*****

Confederate officials ordered much of the CSA currency in government hands burned as they fled Richmond in April 1865. Still, thousands of bills already in circulation survived the war to be preserved as painful momentos of a valiant but doomed enterprise.

Time passed and a new generation prized Civil War artifacts for their historical value. Confederate bills gained new value for collectors, who sought to learn all they could about the individual bills. Although the female image on the $1.00 bills was not recognized by most collectors, a moderate amount of research done by H. D. Allen authenticated it as being that of Lucy Pickens.

Establishing the identity of the feminine image on the $100 bills, however, proved more difficult. Most people assumed Varina Davis, wife of CSA President Jefferson Davis, had been the model, probably because she was the best-known Southern woman. However, after months of investigation, that included gathering affidavits from friends and relatives of both Mrs. Pickens and Mrs. Davis, Allen established that Lucy Pickens is featured on the $100 bills issued in December 1862, April 1863, and December 1864. He published his findings in a series of articles in Volume 31 (1918) of The Numismatist.

Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara may always be the feminine face of the South for the majority of Americans, but serious students of the Civil War know that the title belongs to Lucy Holcombe Pickens.

Enjoyed your article a lot.