A Loyal Soldier’s Legacy

A Union veteran found a unique way to honor his fallen Commander-in-Chief.

Among the nearly five thousand casualties of the July 1861 Battle of Bull Run was the romantic notion that the conflict between the states would be short-lived. President Abraham Lincoln responded to the disastrous first battle by issuing a call for 500,000 troops to serve a three-year commitment.

An eighteen-year-old farm boy from Kendall County answered the call of his fellow Illinoian by enlisting in the Thirty-sixth Illinois Volunteer Infantry. James E. Moss was mustered in as a member of Company E on September 23rd.

After training in Rolla, Missouri, young Moss found himself in the thick of the war in the west as the Thirty-sixth helped secure Union victories at Pea Ridge in Arkansas, Perryville in Kentucky, and Stone’s River in Tennessee. Eighteen members of Company E were killed, wounded, or captured in the Union defeat at Chickamauga in September 1863. Moss, however, was among those who retreated into Chattanooga and lived on short rations as Confederates besieged the city.

The tide turned again on November 23 when U. S. Grant launched an initiative to drive General Braxton Bragg’s rebels from strongholds around Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain fell to the Union on the 24th; on the 25th the Army of the Cumberland, including the Thirty-sixth Illinois, made its legendary ascent of Missionary Ridge. Unfortunately, Moss was not among the jubliant Yanks who watched the Rebs flee deeper into Georgia: A minie ball shattered his left leg before he reached the top of the ridge.

The Thirty-sixth Illinois went on to fight in Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign and the battles of Franklin and Nashville, but Moss had fought his last battle. His leg amputated below the knee, he was sent back to Illinois to recover. Ten months after being wounded, Moss was granted a disability discharge on September 29, 1864.

*****

November 25, 1923

This is the 60th anniversary of the Battle of Missionary Ridge, and as I arose from my bed, thought I ought to write of my personal recollections, as it was the beginning of a new experience, one that was to follow me through life, that of being a cripple the rest of my days.

This paragraph opens James E. Moss’s account* of being wounded, having his leg amputated, and being moved from Chattanooga to Illinois. Describing himself as a cripple may have surprised those who knew him, as his post war life was characterized by energy and achievement in various spheres.

The Greene Co Farm Directory Bios says Moss, who left the army with the rank of Corporal, $600, and a wooden leg, worked as a farm laborer. When he married in 1867, he was earning $15 a month. A good businessman, he bought eighty acres of land, sold it for a profit, and in 1875 used the proceeds as a down payment on 480 acres of unimproved land in Greene County, Iowa. He returned to Illinois but in 1879 moved his family to the property near Scranton. His biography in Volume III of Iowa: Its History and Tradition notes that Moss erected a home and outbuildings and began a sucessful farming operation that eventually spanned 1,000 acres.

Fertile prairie soil and a sound business sense combined to make Moss

a prominent individual in Greene County. The United States Census of 1880 shows Moss as the head of a household including his wife, three young daughters, a nephew, a servant girl, and three hired men. The Biographical and Historical Record of Greene and Carroll Counties, Iowa says Moss had “a fine two-story residence, well furnished, a large, commodious barn, and numerous other out-buildings for stock and grain, a grove of 6,000 trees, [and] an orchard. . . .”

Moss chose his stock carefully. According to Iowa: Its History and Tradition, he raised “full blooded shorthorn cattle and Poland China hogs” and introduced “percheron stallions into Greene county.” In 1887, the Biographical and Historical Record identified Moss as president of the Scranton Norman Horse Company, an organization dedicated to breeding high-quality horses for farm work.

Moss’s progressive efforts went beyond agriculture. Iowa: Its History and Tradition notes that when Moss retired in 1900 and moved into Scranton, he modernized his home by installing a water heating system and gas lighting. His interest in new and better methods remained unfazed by his retirement, and he later helped organize Scranton’s first electric and telephone companies.

Although Moss always seemed to look to the future, he recalled his Civil War service with pride. He was a member of the N. H. Powers GAR Post, attended reunions of his company, and revisited some of the fields where he had fought for Lincoln’s goal of preserving the Union. In 1913 events appealing to both of these aspects of Moss’s character transpired.

In that year a cadre of automotive entrepenuers envisioned a transcontinenal motor route to promote better roadways. (Ninety percent of American roads were little more than dirt trails.) If successful, the route would not only enhance automobile sales but also provide business opportunities to the communities through which it ran. The group called itself the Lincoln Highway Association. The name became a great marketing tool in that it took advantage of Lincoln’s enormous popularity and alluded to the slain president’s interest in national infrastructure. (Lincoln had supported improved waterways and the transcontinental railroad.) Also in 1913, the LHA announced its route. The nation’s first cross-country highway would run through Scranton, Iowa. North of town, it would run along the east side of James Moss’s property then turn west at a right angle.

The Lincoln Highway ran from New York City to San Francisco, primarily on a network of existing roads drivers navigated by observing red, white, and blue signs marked with a large capital L. The roads were graded and graveled. In addition, mile-long “seed roads” were inserted at intervals to demonstrate the advantages of concrete and spur states to invest in hard surfaced roadways.

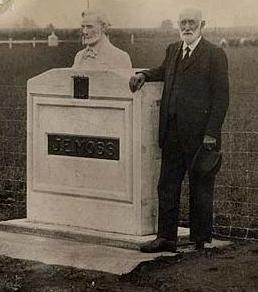

James E. Moss posing beside one of the monuments to Abraham Lincoln he placed along the Lincoln Highway near Scranton, Iowa when the road was paved in 1924. The back of the second monument can be seen in the upper left of the photograph. Also visible is the wooden leg Moss wore after the amputation of his left leg following the Battle of Missionary Ridge in 1863.

Unfortunately, World War I put the brakes on the Lincoln Highway, and it was the 1920s before Greene County paved the highway near Scranton. To facilitate better traffic flow, the Iowa Highway Commission proposed curving the road around Moss’s property and approached him about selling the necessary acerage to accommodate the change. Moss’s reply must have surprised the Commission: He would donate the land if he were permitted to erect a monument to Abraham Lincoln at each end of the curve. The IHC accepted his gift and his conditions.

Moss commissioned Tom Carlisle, a Greene County art student, to create two identical busts of Lincoln. The busts were mounted on large bases bearing the L logo of the Lincoln Highway. Moss’s own name appeared in large letters across the bases. Numerous dignitaries and some of Moss’s cattle witnessed a dedication ceremony for the monuments in 1924.

Moss surely felt his tribute to Abraham Lincoln would be viewed by thousands of motorists for many years, but a series of events nearly relegated them to obscurity. In 1925, highways in the United States became identified by numbers rather than names. The Lincoln Highway became U.S. 30 and was eventually rerouted south of the Moss farm. Finally, sometime in the 1950s, vandals removed the Lincoln busts from their bases.

Another series of events forty years later put the Moss monumets back into the spotlight. One was the emergence of a new Lincoln Highway Association comprised of individuals dedicated to preserving and promoting what remained of the original route and businesses it engendered. Also in the 1990s, one of the original busts was discovered. A mold made from it was used to cast two new busts which were mounted on the original bases. A rededication ceremony for the landmarks was held July 27, 2001, seventy-seven years after James Moss dedicated them to his beloved commander-in-chief.

Lincoln Highway signs along U. S. 30 north of Scranton direct history buffs to James E. Moss’s tribute to Abraham Lincoln. Descendants of the Civil War soldier paid for the restoration of the twin monuments, which were rededicated in 2001.

Today motorists crossing Iowa on U. S. 30 are invited to make detours into history. As a result of the Lincoln Highway Heritage program, signs indicate locations of the remaining portions of the Lincoln Highway in Iowa, an amazing 85% of the original route. North of Scranton, one of the familiar red, white, and blue signs guides motorists to what locals call Moss Corner.

_____

* Moss’s complete account can be found on the FLETCHER MOSS SHREVES BLOG