Horse Story or Tall Tale?

The September 1931 issue of The Palimpsest, a publication of the Iowa State Historical Society, includes an article by O. A. Garretson. Entitled “A Famous War Horse,” it tells of soldiers from the Fouteenth Iowa Volunteer Infantry removing a horse from a Louisiana plantation to give their colonel, J. H. Newbold, whose horse had developed an eye infection. Colonel Newbold was killed a few days later on April 9, 1864, while riding his new mount in the battle of Pleasant Hill. The horse was unhurt, and Captain Warren C. Jones, who assumed command upon Newbold’s death, rode it through the rest of the battle.

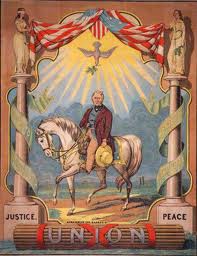

The horse that went from barn to battlefield, according to Garretson, was Old Whitey, the horse ridden by General Zachary Taylor during the Mexican war, pictured on his 1848 campaign posters, and pastured on the White House lawn during his presidency.

Shortly after the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Garretson asserts, Old Whitey was shipped up the Mississippi to Keokuk , taken overland to Mount Pleasant and presented to Newbold’s widow. Supposedly, the famous war horse was made to suffer the indignities of farm work before being purchased by Captain Jones, who ” tenderly cared for ‘Old Whitey’ as long as the thoroughbred lived and at the end buried him with military honors a mile and a half north of Mount Pleasant.”

Seeking to verify the story and learn the exact location of the grave, I telephoned the Mount Pleasant Chamber of Commerce/Tourism Office. The woman who answered knew nothing about a nineteenth-century horse grave but referred me to the Henry County Historical Society which has launched an ambitious sesquicentennial observance focusing on area soldiers. The HCHS members I called and e-mailed were also unaware of this horse story.

I next turned to the records of the Fourteenth Iowa and learned that between March 10 and May 22, 1864, the regiment had participated in General Nathaniel Banks’ Red River Campaign, including the Battle of Pleasant Hill where it suffered heavy casualities, one being the death of Colonel Newbold. Captain Jones did assume command and wrote the Official Report of the battle. Simply put, the Fourteenth was exactly where Garretson says it was.

However, Garretson adds that “on the twenty-mile march from Alexandria to Cotile Landing, a squad of soldiers of the Fourteenth . . . were out on a foraging expedition” when “they arrived at a very aristocratic plantation.” There they “discovered a beautiful white horse” which they decided to take for Newbold’s use. According to Garretson, “the lady of the house” identified herself as the wife of CSA General Richard Taylor and pleaded with the soldiers to leave the horse because it “was the one that General [Zachary] Taylor had captured from a Mexican officer and had ridden during most of his campaigns in the Mexican War.”

At this point, I consulted a variety of sources to test the rest of the story. Most of what I learned contradicted Garretson’s account.

In Letters from the Frontiers, career soldier George Archibald McCall, writes that he acquired the white horse in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1838 after being assigned to relocate Cherokee Indians from Tennessee to Oklahoma territory, where he was stationed at Fort Gibson for three years. McCall says that when his regiment was ordered to Florida in 1841, General Taylor rode from his headquarters at nearby Fort Smith, Arkansas, to inspect it. Taylor saw the horse, liked it, and offered to buy it. McCall, who would go on to serve in both the Mexican War and the Civil War, agreed. His account contradicts Garretson’s on the issue of how Taylor acquired Old Whitey.

Other descrepancies involve the Taylor plantation. Garretson’s story takes place in northwest Louisiana. Richard Taylor’s plantation, called Fashion, was located in St. Charles Parish, about 30 miles from New Orleans. In April of 1862, after New Orleans fell to Union control, soldiers from the Eighth Vermont Volunteers ransacked it and other plantations in the area. According to T. Michael Parrish, author of Richard Taylor: Soldier Prince of Dixie, Fashion “suffered some of the worst desceration and looting,” including soldiers’ carrying off documents, clothing, and even the ceremonial sword that had belonged to President Taylor. None of the Taylors were on the plantation at the time. Richard Taylor was with the Confederate army in the Shenandoah Valley. When he left for the East, Mrs. Taylor and the children went to live at her mother’s home in New Orleans. They left the city via steamboat ahead of the invading Yankees. In the spring of 1864, they were in Shreveport.

Finally, it is unlikely that Old Whitey survived until 1864. McCall claimed the horse was four years old when he bought it in 1838. Granted, horses often live longer than thirty, meaning Whitey could have been among the 130 horses Parrish says the Federals removed from Fashion. However, an article in the January 1897 The Outlook strongly suggests an antebellum demise. In “Famous American War Horses,” General James G. Wilson includes a quotation from “the last survivor of General Taylor’s family,” who would have been the general’s youngest daughter, Mary Elizabeth Taylor Bliss Dandridge:

You ask about Old Whitey; he was a great pet to us all, and was never ridden after my father’s return from Mexico, and when he went to Washington the horse was sent to his plantation. During his term as President there was so much interest and curiosity expressed to see the old charger that he had him brought to Washington, and after my father’s death, he was sent back to the plantation, then the home of my brother Richard, where Whitey lived to a good old age.

“A Famous War Horse,” therefore, appears to contain a considerable amount of codswallap, a surprising condition for an article appearing in The Palimpsest (now the Iowa Journal of History and Politics) and written by an author of good repute. O. A. Garretson was a respected citizen of Henry County who, over the course of his seven decades, held numerous local offices and served on the board of his alma mater, Whittier College, a Quaker school in Salem, Iowa. During World War I, he served as the local Fuel Administrator and worked with the Liberty Loans program. Considered an authority on southeast Iowa, he contributed numerous articles to The Palimpsest between 1920 and his death in 1933.

Given his background, it is unlikely Garretson would have knowingly presented a false story. (As noted earlier, his description of the movements of the Fourteenth is accurate.) It is plausible, however, that Garretson was misinformed on issues he would have had difficulty researching in a pre-Internet world. His article contains no direct quotations, an indication that he probably based it on hearsay rather than interviews. Fifty years of retellings could turn any light-colored horse from Louisiana into Old Whitey. Or, perhaps, some quick-thinking woman owning an old white horse claimed it was Old Whitey in the hope Federal soldiers would revere the aging steed of a former Commander-in-Chief and not take it into battle. (A painting of General Winfield Scott was the one item at Fashion left intact by the Eighth Vermont.) Or maybe a soldier in the Fourteenth made up the story to impress a young lady. Perhaps . . . . . .

The possibilities about what happened are endless, but odds are that if a horse captured in Louisiana lies buried in Henry County, Iowa, it isn’t Old Whitey.