A Widower’s Legacy

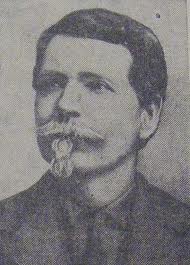

As a young man in a southern state, William Smart acted on his loyalty to the Union. As a middle-aged widower, he demonstated his devotion to his children.

Arkansas seceeded from the United States on May 6, 1861. Most of her young men joined rebel units, but Union loyalists eventually fielded eleven infantry and four cavalry regiments, along with two artillery batteries.

One of the latter, the First Arkansas Light Artillery, was raised in Fayetteville in the spring of 1863. William Jackson Smart, a few months shy of his twenty-first birthday, crossed the state from his home along the Mississippi River to Fayetteville in its northwest corner to enlist. He mustered in with the rank of Corporal.

The Union victory at Pea Ridge in March 1862 forced the Confederates east across the Mississippi, leaving Missouri and Arkansas in Union hands. When the Union First Arkansas Light Artillery was formed a year later, its purpose was to help control Confederate guerrilla activity in Arkansas, southern Missouri, and Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The unit engaged in no major battles, but moving guns through the rugged Arkansas terrain, often in inclement weather, was always arduous and often dangerous. Garrison duty at Fort Smith in Arkansas and Fort Gibson in Indian Territory late in the war proved less challenging– to the point of boredom. Whatever his duties, William Smart performed them well, mustering out in August 1865 as a Sergeant.

Physical labor and responsible behavior characterized Smart’s postwar life as well. In 1865 he returned to east Arkansas, married 17-year-old Elizabeth Harris, and took up farming. The couple had several children, at least one of whom died in infancy, before Elizabeth died in 1878. Approximately two years later, Smart married Ellen Victoria Cheek Billingsley, a 29-year-old widow with three children. Patrick Browne, author of the blog Historical Digression, says that Smart also supported a widowed sister and her child for a time.

Smart’s family responsibilities increased with the birth of a daughter, Sonora Louise, on February 18, 1882. By 1887, when Smart moved his family to rural Washington, three more children, all sons, had been born. Two more boys were born after the family settled on a farm between Creston and Wilbur, near Spokane.

At this point the story becomes muddled. Many sources claim that Ellen Smart died giving birth to her ninth child (her sixth with William Smart). However, Ellen’s death date is always listed as 1898, and that date appears on her headstone, pictured on the Find A Grave website. The birth date of her last child, Thomas Fred Smart, is given as 1891 on his gravestone, also pictured on Find A Grave. Therefore, Ellen either died in childbirth in 1898 but the child did not survive, or she died of another cause.

In either case, at age 56, William Smart was once again a widower, responsible for the care and support of his six youngest children, his adult children and stepchildren having established their own households. Initially Smart may have relied on Sonora, sixteen years old at the time of her mother’s death, to perform many household tasks. When she married in 1899, he reared his five boys alone.

Inspired by love for her own father, Senora Smart Dodd waged a decades-long campaign to have Father’s Day declared a national holiday.

On a spring Sunday in 1909, 27-year-old Sonora Smart Dodd sat in church listening to a Mother’s Day sermon. It undoubtedly evoked memories of her deceased mother. It may have caused her to contemplate her responsibilities to her soon-to-be-born child. Most of all, it prompted an appreciation of her father, William Smart, for providing a loving and nurturing home for her and her siblings after their mother died. She decided that fathers, as well as mothers, deserved a special day of recognition.

Sonora took steps to bring her idea to fruition. She prevailed upon her minister to submit a resolution for a Father’s Day observance to the Spokane Ministerial Association at its meeting on June 6, 1910. The resolution was approved, and Spokane’s mayor and Washington’s governor proclaimed June 19, 1910 as a day to honor fathers.

Ministers prepared sermons, shopkeepers displayed father-appropriate gifts in their windows, and the young women’s group of Sonora’s church– the Old Centenary Presbyterian Church– bought red roses to give to the fathers. Presumably, one was meant for William Smart. On June 19, other churches in Spokane passed baskets of red and white roses among attendees. Those whose fathers were deceased were asked to wear white roses, while those with living fathers were to wear red. Sonora took Father’s Day gifts to Spokane shut-ins.

Sonora Dodd was not the first person in the United States to organize a Father’s Day, but earlier observances had been local events. Spokane’s celebration was reported in major newspapers, resulting in Sonora’s receiving hundreds of letters of support. Gradually the concept caught on, and other Father’s Days were observed across the country. Father’s Day became popular, but it was not a national holiday. Sonora Dodd thought it should be.

From William Smart, Sonora inherited qualities of perseverance and determination, and she was an articulate individual. (She later became, among other things, a published author and a member of International Toastmistresses.) She drew upon her skills and contacts to promote Father’s Day at the highest levels, but progress was agonizingly slow. Some members of Congress considered such an observance unmasculine; others felt it would promote commercialism.

Opinions gradually changed. According to the Spokane Regional Covention & Visitor Bureau, President Woodrow Wilson “officially open[ed] Father’s Day services from his office in Washington, D. C.” in 1916. Eight years later, President Calvin Coolidge supported the concept of Father’s Day, but felt the individual states should determine its observance. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed a proclamation designating the third Sunday in June that year as Father’s Day. In December of 1970, a Joint Resolution of Congress asked President Richard Nixon to make a similar proclamation. In 1972, Nixon signed a proclamation designating each third Sunday in June as Father’s Day, making official the tradition started by Sonora Dodd sixty-two years earlier.

William Jackson Smart died in 1919, aware of his daughter’s desire to have fathers acknowledged yearly nationwide. Sonora Dodd died in 1978, six years after winning her battle to honor fathers, especially her own.

*****

This article is one of series dedicated to acknowledging the contributions made by survivors of the Civil War. To see others in the series, click on Survivors’ Legacies on the left side or top of the home page.