Shared Misery, Divergent Lives: A Look at Two of “The Immortal Six Hundred” Part II

For captured Confederates Junius Hempstead and Barney Cannoy, Fort Delaware marked the beginning and end of an odyssey of suffering.

Part II: Prisoners, 1864-1865

Both Junius Hempstead and Barney Cannoy, Confederate soldiers captured in General U. S. Grant’s Wilderness and Spotsylvania campaigns, arrived at the Ft. Delaware prison camp on May 17, 1864. Nine days later, Major General John G. Foster assumed command of the Union’s Department of the South, comprised of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. None of the three men knew these events would converge in one of the most brutal stories of the Civil War.

*****

Commander Foster set his sights on Charleston, South Carolina. The city where the war began remained an open port, an embarrassing gap in the Union naval blocade, and rebel-held Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was an unhealed lesion on Union pride. For Foster, who had been among the small band of soldiers in the fort during its bombardment and surrender in April 1861, the wound was especially deep.

Regaining Sumter and bringing secessionist Charleston under Union control had long been been a goal of the U. S military. By the time Foster took command, Morris Island at the southeast end of Charleston Harbor had been under Union control for several months. From it, Union artillerists daily lobbed barrages of shells toward Sumter and the city. Still, the city, the inner harbor, and Fort Sumter remained in rebel hands. Foster, determined to conquer Charleston, placed more guns on Morris Island, brought more gunboats into the harbor, and continued shelling the city.

Charlestonians’ concern about shells in residential areas prompted Confederate commander Major General Sam Jones to inform Foster that no military sites existed in some of the targeted sectors. Rather than agreeing to redirect his fire, Foster replied “Charleston must be considered a place of arms” and that danger to women and children is simply a part of war.

Jones, in an effort to protect civilians, suggested to his superior, General Braxton Bragg, that housing prisoners in a residential area might persuade Foster to stop “endangering the lives of women and children.” As a result, fifty high-ranking Union offiers were brought to Charleston and confined in a comfortable private home near a marked hospital, a location normally presumed a safe area. “It is proper . . .,” Jones wrote to Foster on June 13, “that I should inform you that it is a part of the city which has been for many months exposed day and night to the fire of your guns.”

Foster’s reply was not concilliatory. He refused to stop the shelling and announced plans to place fifty rebel officers “in positions exposed to the fire of your [Confederate] guns.” Jones responded, in essence, that Foster was comparing apples to oranges because all Confederate guns were aimed at military targets since the Union had no civilian presence at Charleston.

Jones’s logic was lost on Foster, who called for fifty rebel officers to be moved from the Union prison at Fort Delaware to Charleston and housed at dangerous locations. Upon learning their Confederate counterparts were being so exposed, the Union captives wrote to Foster, explaining that they were being well treated and not “unnecessarily exposed to fire.” They implored him to treat the Confederate officers in a like manner.

At this time in the war, prisoner exchanges had slowed to a trickle. Members of the Lincoln administration and General Grant believed ceasing exchanges would shorten the war. With most southern men between the ages of 17 and 45 already in service, the CSA forces were weakening. Preventing experienced soldiers from returning to the ranks would be advantageous.

However, the concept of using prisoners as human shields was so outrageous to both sides that within three weeks official agents agreed to exchange the hundred officers. The event was formally marked with a suspension of shelling (except for celebratory salutes) and a banquet attended by the hundred officers and various dignitaries. This episode, unfortunately, was merely the opening act for a large-scale production that would not have a happy ending.

Shortly after the exchange, General Jones received news of Union prisoners from Andersonville and Macon being moved to Charleston to avoid their being liberated in Sherman’s Georgia campaign. Jones was appalled because he lacked accommodations and manpower to handle a large number of prisoners. His appeals to Richmond resulted in a good news/bad news response: New prison camps were being built farther inland, but until they were completed, 600 Union prisoners would stay in Charleston.

When Foster heard of the presence of the Union prisoners, he angrily assumed Jones had again opted to use prisoners as shields. Jones, of course, described his circumstances to Foster, who then acknowledged to Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck that the prisoners were “merely enroute” and that he knew “their exact position and [would] direct the shells accordingly” to avoid endangering them. Nevertheless, he asked permission to have Confederate prisoners brought to Charleston, proposing to place them “immediately on[the north end of] Morris Island between [batteries] Wagner and Gregg.” Amazingly, Halleck and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton approved his request for human shield prisoners.

On August 13, 600 Confederate officers imprisoned at Fort Delaware– mostly junior officers promoted for battlefield conduct– heard their names read from a list and assumed they were going to be exchanged, lieutenants Cannoy and Hempstead among them. Selection criteria for the list remains unknown, but all 14 states that raised Confederate regiments, regardless of secession, were represented. Hempstead and Cannoy were among 186 soldiers from Virginia.

A week later, the 600 hopeful Confederate officers walked through the sally port of Fort Delaware into hell in the form the Crescent City, a converted cargo steamer. On board they were confined in the hold which had been fitted with three tiers of crude bunks on each side. As many as four prisoners shared a single bunk.

Very little light reached the hold, as guards permitted only one hatch to be open, and the upper bunks blocked light from the portholes. Hot August weather and heat from the boiler sent temperatures inside the hold soaring.

Before long, many prisoners became seasick, and soon the hold was filled with the stench and slime of vomit and excrement. The only water available to the prisoners was hot water from a condenser. Guards refused repeated requests for the hold to be hosed out with sea water.

The Crescent City crawled southward, stopping at Fortress Monroe on the Virginia peninsula on the second day. The hopes of Cannoy, Hempstead, and their comrades fell when guards informed them that the place of exchange had been changed to Charleston. They began to realize their guards were playing a cruel joke on them and that they were not going to be exchanged.

Therefore, when the Crescent City ran aground forty miles north of Charleston on the night of August 23-24, the prisoners attempted an impromtu takeover of the steamer. It may have succeeded if the gunboats escorting the steamer had not appeared.

Perhaps as punishment for the attempted mutiny, or perhaps because their guards took delight in cruelty, the prisoners’ meagre rations of food and water vanished. Fortunately, on August 27th when the steamer reached Foster’s headquarters at Hilton Head, new guards took charge of the 600 and treated them with compassion. The hold was cleaned, food and water were provided, and a young Union officer acted as purchasing agent for the prisoners, buying items on shore for those who had money or valuables for credit. The new guards also removed forty sick rebel officers and sent them to a Federal military hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina.

Finally, the Crescent City steamed back north, reached Lighthouse Inlet on the south end of Morris Island on September 7, and deposited the 560 remaining prisoners ashore. Escorted by members of the 54th Massachusetts United States Colored Troops, the weakened Confederates marched over two miles in rain to their new home– an open stockade in the sand. Two-man A-tents were their only shelter from blazing sun and pouring rain.Four men were assigned to each tent.

Guards searched the few possessions the prisoners had with them. In 1893, J .L. Lemon, one of the captives, recalled that “all U. S. blankets, clothing, canteens, and . . . trinkets marked U. S.” were seized, “leaving some of our men nearly bare.” Whether lieutenants Hempstead and Cannoy had any such items is not known, but each had at least one important personal item left unconfiscated. Cannoy was permitted to keep a small kettle, while Hempstead retained a rhetoric text he had brought from Iowa.

Conditions aboard the Crescent City had kept the prisoners from keeping diaries, but at Morris Island, several men recorded their experiences. Hempstead used blank spaces in his rhetoric book for that purpose. His first entry described the rebels’ entrance into the stockade:

[The negro guards] marched us by detachments to the pen where we founds tents put up in regular order I am in Comp. “D” No 3 Saw some huge guns one was eighteen feet long and three feet diameter at the breech.

The prisoners wrote and sent letters as well. On September 28, Lieutenant Earl Andis, a member of Cannoy’s Grayson Daredevils, wrote to his wife, asking her to send “five or ten dollars in Federal Green Backs” to him, adding “Lieut. B. B. Cannoy is here with me and is well.”

The guns Hempstead described in his diary were in Battery Wagner, which the prisoners had passed on their way to the stockade. Similar weapons were also in Battery Gregg, slightly north of the camp. Both batteries fired shells toward Fort Sumter, those from Battery Wagner going over the heads of the prisoners. Rebel guns from Fort Sumter and Sullivan’s Island returned fire. Although the stockade was not a target and the Confederate batteries took care to avoid firing toward it once gunners learned of the prisoners, it was, nonetheless, a dangerous place. A number of guards outside the pen were struck by shrapnel, and numerous dud shells fell among the prisoners but did no harm.

Shelling had a mostly psychological effect on the prisoners, but plenty of physical danger came from other sources. The flimsy tents provided little protection from sun, rain, and wind. Biting sand fleas and mosquitoes constantly swarmed the prisoners. For drinking, cooking, and bathing, the captives collected rain water and dug into the sand in hopes of finding water. Food rations were few and poor, generally consisting of small portions of wormy hardtack and watery soup or rice. Amost every entry in Hempstead’s diary tells of deprivation and hunger. Three prisoners died of disease and/or starvation.

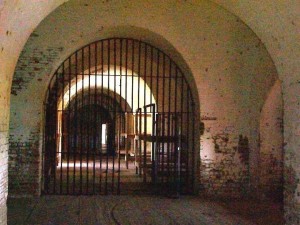

On October 8, the Union prisoners in Charleston were taken to new prison camps. On the 21st, after enduring 45 days on Morris Island, the remaining Confederate prisoners were transferred to Fort Pulaski at Savannah. There they were incarcerated in open casemates equipped with bunks made of rough planks.

Guns were removed from casemates and iron gates added to create cells for rebel prisoners at Fort Pulaski.

The Federal officer in charge of Fort Pulaski when the prisoners arrived was Colonel Philip Brown, a compassionate man whom the captives liked. Initially, he restored them to full rations and allowed them privileges. He was, however, somewhat timid and followed orders doggedly. When Commander Foster determined that the captives should be treated in the same manner as Union prisoners at Andersonville, Brown changed their diet to moldy cornmeal and pickles. Whenever possible, the men augmented their diet with dogs and cats that wandered into the prison; eventually, they resorted to catching rats.

In using the men as retaliation prisoners, Foster ignored the fact that Union policies had made it impossible for the Confederacy to feed its soldiers well, much less their prisoners. He was taking out his misguided vengeance on innocent men.

The prisoners no longer had to suffer from the heat at Fort Pulaski, where cold combined with malnutrition and disease to test their mettle during the exceptionally harsh winter of 1864-65. They had been issued no blankets or winter clothing.

Somehow in moving from Morris Island to Fort Pulaski, Hempstead lost his rhetoric book/diary.* Cannoy kept his kettle. They, like most of the prisoners, probably wrote letters to loved ones at home. In a letter dated October 26, Andis told his wife he and Cannoy had “very good quarters in the Fort.” A week later, he wrote that Cannoy had received a letter from his father forwarded from Fort Delaware. Later, probably under Foster’s orders, guards routinely destroyed the prisoners’ outgoing letters.

Hempstead’s background as the son of a former Iowa governor made him something of a celebrity. On December 29, William M. Stone, the newly-elected governor of Iowa, accompanied by a journalist from the Dubuque Daily Times visited Hempstead on behalf of an Iowan concerned about the young man. The journalist made the following report regarding Hempstead to his editor:

He was comfortably clothed and in good health. He talked an hour or so with the governor and other gentlemen who had been in the Army, and was very communicative about Rebel affairs. He has refused I believe to take the oath of allegiance to the United States. He is quite young . . . but seems to have good sense enough. The Company blamed rather his education, than himself for the fact of his having taken up arms against his country, therefore ruining himself in the estimation of all right thinking men.

During their ordeal, any of the 600 would have been released had they taken the oath of allegiance to the United States. Very few men did, and they were looked upon with disfavor by the majority who had formed a strong bond to help each other survive. Stronger men shared their pitifully small rations with weaker comrades. On especially cold nights, those who could walk paced all night to keep from freezing to death after covering feebler bunk-bound friends with their flimsy blankets. When the fort’s doctor was forbidden to prescribe curative medicines and could provide only opiates to lessen sick prisoners’ pain, healthier men feigned illnesses in order to obtain drugs for addicted peers too weak to survive going through withdrawl.

Hempstead’s efforts to help others were many and appreciated. Captain J. Ogden Murray, who coined the term the Immortal Six-Hundred and used it as the title of his 1905 book, wrote, ” [Hempstead’s] heart went out in sympathy to his suffering comrades, his generous hand had relieved their wants from his scanty ration.” Scorned for his lack of military acumen at Gettysburg, Hempstead earned the respect of his fellow prisoners.

On November 19, 197 of the Immortal 600 were moved to Hilton Head to relieve crowding in the casemates at Fort Pulaski. Still, the sense of comaradarie among the prisoners was so great the separation was painful.

Cannoy and Hempstead were among the prisoners destined to endure a frigid winter at Fort Pulaski. Thirteen of their commrads did not live to see March 12, 1865, when the surviving emaciated men were returned to Fort Delaware.

Although prisoner exchanges resumed as the war drew to an end, the remnants of the Immortal 600 remained at Fort Delaware into the summer. Some believe United States’ officials did not want them released until they could be fed and given medical care so that they did not resemble their Union counterparts, the human skeletons from Andersonville.

On June 16, 1865, Barney Cannoy took the oath, was released from Fort Delaware, and returned to his home in Elk Creek, Virginia, carrying his well-traveled kettle. A few days earlier, Junius Hempstead had followed a similar pattern and returned to Dubuque, Iowa. They would not see each other again, but they– and others of the 600– would always share a bond born of endurance.

_____

* After many years, the book was found and returned to Hempstead’s family. An article entitled “How long will this misery continue” in the February 1981 issue of Civil War Times Illustrated contains many excerpts from Hempstead’s diary. The article was edited by Bess Beatty and Judy Caprio.

*****

Author’s Note

You have just read a brief summary of the imprisonment of the men now known as The Immortal 600. You have much more to learn about them and can benefit from the following resources:

-

Captives Immortal: The Story of Six Hundred Confederate Officers and the United States Prisoner of War Policy by Mauriel Phillips Joslyn. This comprehensive analysis of the prisoners and the politics impacting them blends first-person accounts of the prisoners and their captors with information from military and administrative records. Its companion book, The Biographical Roster of the Immortal 600, contains the names and military records of the prisoners. These volumes are factual and impartial.

-

War of Vengeance: Acts of Retaliation by Lonnie R. Speer. This book is also well-researched and factual.

-

Immortal Six-Hundred by John Ogden Murray. Published in 1905 by one of the prisoners, this book contains personal observations of the author and is written in the style of nineteenth-century literature.

- Facebook. Join the Immortal 600 group!

- The Internet. More and more articles are being added.

Please also read

Part I: Soldiers

Part III: Civilians

.