Separate Lives, Shared Misery: A Look at Two of the “Immortal Six Hundred” Part I

Had it not been for the Civil War, Barney Cannoy and Junius Hempstead would have continued living in separate worlds, but a Union general’s obsession brought them together in one of the war’s most infamous imprisonments.

Part I: Soldiers, 1860-1864

Autumn 1860

Among the students entering the Virginia Military Institute at Lexington in August, 1860, was a 17-year-old Iowan, Junius Lackland Hempstead.

Blessed with artistic abilities, the young man from Dubuque had won first prize for his marble statuettes in two consecutive years. His work was so impressive that a patron offered to sponsor six years of art education in Europe. However, Junius’s father, Steven Hempstead, declined the offer.

The elder Hempstead had settled in Iowa in 1836 and become its second governer, serving two terms from 1850-1854. In 1855, he was elected as a judge in Dubuque County, a post he was to hold for twelve years. He had, however, spent much of his youth in St. Louis where he studied law. According to his son, he was a “Douglas Democrat” who believed in states’ rights, a position which likely influenced his decision to have Junius schooled in the South, first at Fieldings College in St. Charles, Missouri, then at VMI .

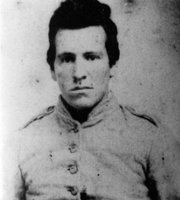

One hundred-forty miles southwest of Lexington, Barney Cannoy labored at the autumnal tasks of farming. Working with his father and younger brothers, he harvested crops, butchered hogs, and chopped wood on the family farm near Elk Creek. When time permitted, he hunted game and fowl in the hills of Grayson County. On November 26, he celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday, his wife and 18-month-old daughter at his side.

Spring 1861 – Spring 1864

Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860, southern states began withdrawing from the Union. Virginia’s secession on April 17, 1861, triggered a series of events that would draw Cannoy and Hempstead into a shared experience of horror.

Almost immediately, military units formed across the state. In Grayson County, 135 young men, mostly farmers, gathered to form the Grayson Daredevils, officially designated as Company F , Fourth Regiment, Virginia Infantry. A creative captain winnowed the number of volunteers to the requisite 100-man company with a shooting competition requiring each man to fire at a target while running. Those who missed the target or hit its periphery were eliminated. Barney Cannoy, whose family now included a month-old son, earned a spot on the Daredevils’ roster.

On April 24, Cannoy and the rest of Company F left Grayson County for Richmond, the assembly point for troops from across Virginia. From there, they marched to Harper’s Ferry, arriving in mid-May.

The outbreak of the war also disrupted life at VMI. On April 20, most of the cadets were ordered to Richmond to serve as artillery instructors and drillmasters for volunteer units– such as the Grayson Daredevils– congregating in the capital city. Despite his northern nativity, Junius Hempstead shared his father’s view of states’ rights, took his cadet oath to support Virginia against her enemies seriously, and remained at the Institute where he was among forty-seven disappointed cadets left to guard the school’s small arsenol.

Hempstead’s frustration at being left behind was short-lived, as he and ten other cadets were soon detailed to escort five gunpowder-laden wagons from Lexington to Harper’s Ferry, a distance of 150 miles. Like the Grayson Daredevils, the cadets marched to Harper’s Ferry. Upon their arrival, the commander of the First Brigade appointed them drillmasters. He was Thomas Jonathan Jackson, who had been one of their instructors only a few weeks earlier.

Hempstead was assigned to Company F, Fifth Virginia Infantry. It, Cannoy’s Fourth Infantry, three additional regiments, and an artillery battery comprised the First Brigade, Virginia Volunteers. Within weeks they would have their first battle experience, and after helping to secure a Confederate victory at First Manassas in July, both Jackson and the brigade carried the Stonewall sobriquet.

Over the next two years, both men participated in major battles in Northern Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Hempstead transferred to the 25th Virginia Regiment and was appointed Third Lieutenant on August 14, 1862. At the Second Battle of Manassas two weeks later, he suffered a shoulder wound which apparently kept him absent from duty until March of 1863. He saw action at Gettysburg in July, later writing “When my cadet comrade Capt. Blankenship lost his leg at Gettysburg, I was made Captain.” Official records, however, state that he was simply the “Acting Commander,” and a member of his company wrote that Hempstead lacked “the sense to drive a lot of ducks to water,” adding ” [t]here is not one in the company that likes him. . .”.

Cannoy, who remained with the Stonewall Brigde, escaped being wounded, although he was hospitalized twice, having contracted typhoid in the fall of 1861 and pneumonia the following spring. On December 31, 1863, he was elected Second Lieutenant.

In March of 1864, Abraham Lincoln elevated Ulysses Grant to supreme commander of all Union armies. Two months later, Grant moved the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac into Virginia, hoping to engage the rebel army in open country south of the Rapidan River.

Robert E. Lee, however, had other plans. Rather than meet Grant in the open where his 66,000-man Army of Northern Virginia would be easily defeated, he opted to entrench his troops in the Wilderness, a wooded area crossed by streams and choked with underbrush that caught fire when the two-day battle began on May 5. Later, Junius Hempstead wrote, “I was wounded and captured on the 5th of May 1864. Our regiment charged into Gen’l Sedgwick’s Corp [sic], and was captured.”

Despite having 17,666 Union troops killed, wounded, or missing in the Battle of the Wilderness, Grant continued to push south toward Spotsylvania Court House. Lee’s army arrived at the crossroads community first, and a fierce 11-day battle began on May 8. Four days into the relentless contest, Barney Cannoy was captured at Spotsylvannia.

Both Cannoy and Hempstead were sent to Fort Delaware, a United States prison camp on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River. Their days in armed combat were over, but soon the vindictive obsession of U. S. Major General John G. Foster would turn every day into a battle for survival.

Please also read

Part II: Prisoners, 1864- 1865

Part III: Civilians