“The World’s Damndest Ass”

As he began his second term in the spring of 1865, President Abraham Lincoln planned two changes in his cabinet. He appointed Hugh McCulloch as Secretary of the Treasury on March 9 and intended to appoint James Harlan, a sitting Iowa Senator, as Secretary of the Interior within a few weeks.

Although Lincoln was assassinated before Harlan could join his cabinet, in May of 1865 Harlan resigned from the Senate to become Secretary of the Interior under Andrew Johnson.

A typical new boss, Harlan vowed to run a tight ship and announced plans to rid his department of non-essential positions. He also vowed to ensure the loyalty of each employee. Harlan’s intentions are easy to understand for the recently-concluded Civil War had drained the country financially, and southern sympathizers had infiltrated Washington. Equally significant is Harlan’s interest in the “moral character” of his employees. It, too, is understandable as Harlan was an ordained Methodist minister.

Harlan made good on his word. Within six weeks, he dismissed numerous staffers. One of them, a 47-year-old second-class clerk in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, protested his firing. His name was Walt Whitman.

Upon receiving his dismissal letter dated June 30, the journalist, poet, and volunteer nurse of wounded soldiers activated his network of somewhat influential friends. The result was a meeting between Assistant Attorney General J. H. Ashton and Secretary Harlan.

When Ashton asked that Whitman be retained, Harlan adamantly refused. Deeming the sexual frankness of The Leaves of Grass morally reprehensible, he not only declined to rehire Whitman but also vowed to resign if President Johnson reinstated him. Additionally, he declared Whitman unfit to work for the government in any capacity. Harlan was so vehement that the best Ashton could do was have him agree not to challenge Whitman’s appointment to another government job. Ashton then arranged for Whitman to became a clerk in the office of the Attorney General, where he remained until 1874.

Harlan’s response to Ashton was a career-damaging tactical mistake in which he confused his ministerial and political roles. He defended his firing of Whitman within the parameters of his Methodist-minister morals. While editions of The Leaves of Grass had been published in 1855, 1856, and 1860, Harlan did not read the controversial book until he discovered a copy on or in Whitman’s desk. Whitman supporters claim Harlan made his discovery during an after-hours prowl through the department when he removed the volume to his own office for examination.

Had Harlan kept his emotions in check and responded to Ashton as a logical, efficient bureaucrat, the incident would probably have been forgotten, as Harlan had numerous objective reasons for dismissing Whitman.

First, Whitman was a recent hire, having joined the Bureau of Indian Affairs on January 24, 1865, only five months before his dismissal. Sometime in March, Whitman asked for and received a furlough to go to his mother’s home in Brooklyn where his brother George, a recently exchanged prisoner of war, was recuperating. Whitman was in New York when Lincoln was assassinated on April 14 and did not return to Washington until following Monday, April 17. Thus, during his five-month stint with the Department of the Interior, Whitman had been at his desk only a little more than four months.

Nor was Whitman putting in long hours when he was on the job, as evidenced by the text of two letters now available online in The Whitman Archive. In a letter dated January 30, 1865, when he had been with the Department less than a week, Whitman wrote to his brother Jeff, “the rule is to come at 9 and go at 4– but I don’t come at 9, and only stay till 4 when I want.” A few days later, he wrote to Abby H. Price, “I have a little employment here, of three or four hours every day.”

If Whitman was expected to be putting in seven-hour days but was coming and going at his discretion, he was insubordinate. If he was being told to report late or leave early, there was clearly little need for his services. In either case, Harlan had irrefutable grounds to dismiss him and could have so informed Ashton. If he chose to reference The Leaves of Grass at all, he could have confined his comments to the handwritten notes Whitman had made in the volume Harlan found in Whitman’s desk. They were revisions planned for the next edition of the book, and they would have been evidence that Whitman was doing personal work on government time. In fact, Harlan later defended his decision by saying Whitman was fired simply because his services were not needed.

However, as often happens when emotion trumps reason, the damage was done. Whitman’s friend William Douglas O’Connor published an emotional essay, “The Good Gray Poet” that villified Harlan while praising Whitman as a poet and a patriot. This time emotions worked in favor of Whitman. Drum Taps, his volume of war poems which came out in May 1865 and When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed, his heartfelt Lincoln elegy, appealed to the partriotic masses who grieved for their fallen soldiers and their commander-in-chief. In addition, even his uninhibited approach to poetry gradually gained acceptance with critics and readers, many of whom had been comforted by his caring presence in the hospitals of Washington during and after the war.

Being known as the man who fired Walt Whitman tarnished Harlan’s reputation to the extent that in 1919, when writing about the event in the Smart Set, H. L. Mencken said, “one day in 1865 brought together the greatest poet America had produced and the world’s damdest ass.”

Some Harlan Trivia

-

Harlan and Lincoln were friends. James Harlan was among the small group to whom Lincoln relayed his prophetic dream of seeing mourners in the White House greiving for their president who had been killed by an assassin.

-

Harlan’s daughter Mary became the wife of Robert Lincoln.

-

Harlan was Iowa’s first State Superintendent of Education as well as the first president of Iowa Wesleyan College. Ironically, the poetry of Walt Whitman is now included in high school and college curricula across the state.

-

Mencken’s assessment of Harlan was addressed by Louis R. Harlan in The Harlan Family in America: A Brief History. With a gentlemanly display of tact, he wrote, “Let us attribute that remark . . . more to Mencken’s admiration of Whitman than as a true characterization of Harlan, whom Mencken never met.”

What You Can Do

- Visit the Harlan-Lincoln House on the campus of Iowa Wesleyan College in Mt. Pleasant, Iowa. Harlan built it as his retirement home, and Mrs. Robert Lincoln and her children spent summers there with her parents.

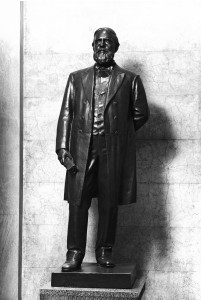

- While on campus, view the statue of Harlan that stood in the National Statuary Hall in the U. S. capitol in Washington, D. C. from 1910 until March of 2014 when it was replaced with a statue of Norman Borlaug.