They Were No Ladies: Part I

We often hear of women disguising themselves as soldiers during the Civil War. Examples of crossdressing men are fewer, but 19th century fashion made it possible for soldiers to appear as ladies.

Mira Madison Alexander, a blind widow in her late fifties, lived in St. Louis in the 1860s. In pleasant weather she enjoyed being driven on outings. Townspeople grew used to Mrs. Alexander, wearing widow’s weeds, her sightless eyes covered by a veil, “seeing” her surroundings via the running commentary of her black driver.

On May 8, 1861, Missouri militiamen training on the outskirts of the city saw Mrs. Alexander’s carriage driving through the streets of their camp. None of them took any particular notice. Had anyone bothered to look closely at the veiled figure, he might have seen a few red whiskers poking through the veil.

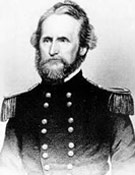

The red beard belonged to Captain Nathaniel Lyon, a feisty career soldier in the United States Army who had served in the Mexican War, fought Indians in the West, and watched Kansas bleed in the aftermath of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The reasons behind his foray into crossdressing begin with Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in November 1860, an event that eventually led to the secession of eleven salve states.

As each withdrew from the Union, the discontented southern states prepared for war by seizing federal property within their borders. Between December 20, when South Carolina seceded, and Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861, seven states in the Deep South controlled over thirty federal facilities including post offices, mints, arsenals, barracks, and every mainland fort on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from South Carolina to Texas.

The seizures were remarkably bloodless for a variety of reasons. Often the military installations were lightly garrisoned. And because James Buchanan– the lamest of lame duck presidents– ambiguously announced that secession was illegal but the federal government had no right to stop it, most military sites were simply handed over to the rebellious states. Civilian workers in facilities such as post offices and mints generally supported the southern cause and happily placed their workplaces under Confederate control– and usually kept their jobs.

In the border state of Missouri feelings regarding secession were less clear-cut. Approximately 25,000 slaveholders lived there, mostly in rural areas along the Missouri River. Governor Claiborne F. Jackson had campaigned on an anti-secessionist platform but did an about-face after taking office in January and declared Missouri’s best interest would be served by aligning with the states of the Deep South.

However, St. Louis, with a population of over 190,000, was a Republican stronghold and the home of U. S. Representative Francis Preston Blair, Jr., of the Blair family which had been behind-the-scenes movers and shakers in American politics for decades. An ardent Unionist, Blair understood that Jackson and his cohorts intended to engineer a secessionist convention and to seize the large federal arsenal at St. Louis. He clandestinely began recruiting fellow unionists, many from the city’s large German population, to begin secret military training.

Captain Lyon, accompanied by 80 infantrymen, arrived in St. Louis in February 1861 to bolster the defense of the arsenal. He soon realized that even with the addition of his company, the arsenal was vulnerable. Unable to convince his superiors to safeguard the facility, Lyon allied with Blair and helped train the latter’s volunteers. Blair, in turn, initiated a flurry of correspondence with his Washington connections that ultimately resulted in Lyon’s being given command of the arsenal.

Tensions between the two factions became critical in April when Governor Jackson refused to comply with Lincoln’s request for Missouri troops to help quell the rebellion in the South. Instead, he ordered the Missouri State Militia into training camps, such as the one on the outskirts of St. Louis known as Camp Jackson. Pro-southern forces secured the United States Arsenal in Liberty and the United States ordnance stores in Kansas City on April 20 and May 4, respectively.

Meanwhile, Lyon and Blair worked with a network of informants who told them armaments seized earlier from the federal arsenal at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, had been sent to St. Louis by the Confederate government. Lyon’s May 8 visit to Camp Jackson in the guise of Mrs. Alexander, who was Blair’s mother-in-law, confirmed the presence of those weapons.

The time had come to act. Washington had finally permitted Blair’s volunteers to be sworn into federal service. On May 10, Union forces commanded by Lyon surrounded the Missouri State Guard militiamen, took them prisoner, and began marching them toward the arsenal.

Unfortunately, this attempt to prevent the seizure of United States property was not bloodless. When soldiers fired into a pro-secessionist mob attempting to disrupt the prisoner transfer, about 20 civilians were killed or wounded. The next day, several citizens were wounded when angry secessionists attacked a regiment of Blair’s Home Guards.

These affairs previewed hundreds of contentious encounters bloodying the border state throughout the war, but Missouri remained in the Union largely because Nathaniel Lyon, looking through Mrs. Alexander’s veil, saw the time was right to keep Governor Jackson’s men from gaining the upper hand.